C++ STL Overview

STL algorithms can make code more expressive

- Raising levels of abstraction

- Sometimes, it can be spectacular.

Avoid common mistakes

- off-by-one

- empty loops

- naive complexity

When writing our own for-loops is about complexity. Some algorithms that they can be implemented naively in quadratic complexity, and in a more astute manner in a linear complexity.

Used by lots of people

- A common vocabulary

- Whatever the version of your compiler

Also, STL algorithms are used by billions of people every day. You don’t need to afraid of them. I think we should level up to STL algorithms and not the other way around.

So even if you are running an older C++ version, you can still get most of the STL algorithms, like for example, if you are in C++03 for example, and you want to use all_of, any_of or none_of which appeared in C++11. Well you can just grab that code, and copy it into your codebase and just start using them. So most of them are within your reach whichever version of C++ you are on right now.

Many more of the STL algorithms that let you express more nuance when you write your code. I’m going to show you something to illustrate the fact that there’s much more than for_each in the STL algorithms library.

Here is the world of C++ STL algorithms

The Queries means the stl algorithms which in this area just extract some piece of information, and they don’t actually modify it. The most of the stl algorithms would somehow change the collection, like sort or partition or whatever. But most of them are just read-only operations.

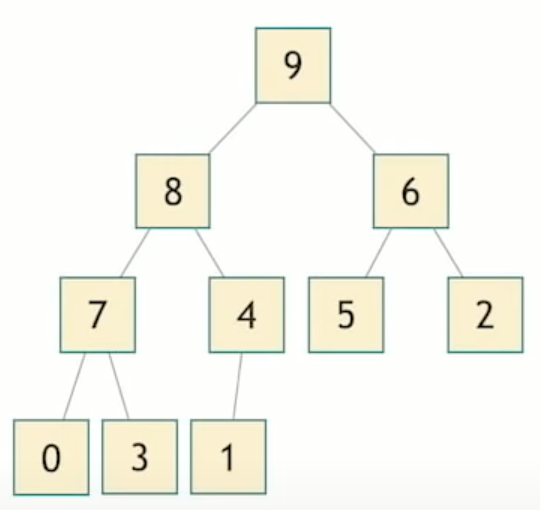

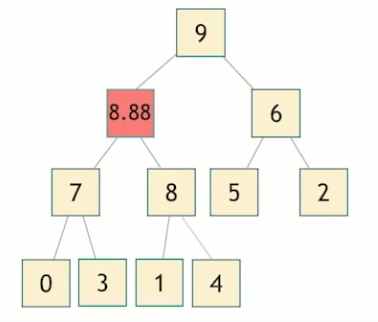

Heaps

A Heap is a data structure that looks like a tree, but that has a property is that every node must be smaller than its children. This is called max heap.

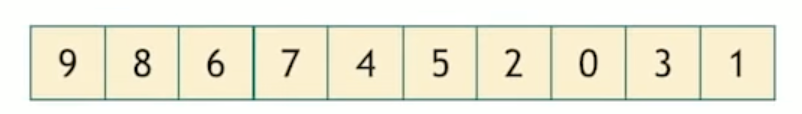

So one extremely interesting property of the heap is taht we can squash it down into a range like below.

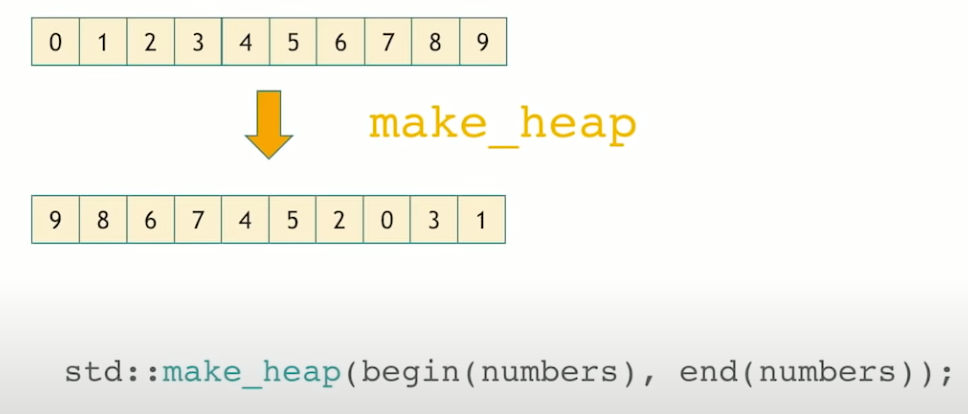

std::make_heap

When you do this, there is a nice property that it’s a range. So we can represent it with a vector, for example which is quite convenient to work with. And also, to go froma node to its left child, it is essentially taking its index and multiplying it by twos, nearly that. So it’s a way to represent a tree into a range. If you have a range, we have a beginning and an end and we can use STL algorithms.

So first thing we can do is taking values that are not particularly a heap, and rearrange them so that they respect the heap property. We use std::make_heap to make a heap. We rearrange the element inside of a collection. This is our first algorithm.

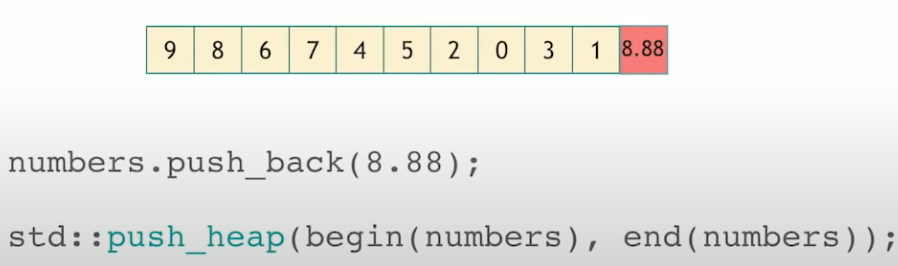

std::push_heap

When we want to add a new value into a heap, we should move up the new value to right position in case to meet the heap criteria.

When we squash the heap into a vector, we add something to the end, and then we need something to make it bubble its way up to its final position, and that is std::push_heap.

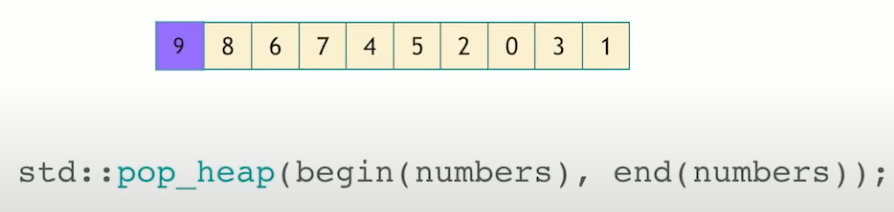

std::pop_heap

When we want to remove something from the heap. Usually we want to get the maximum value from this heap, std::pop_heap can be used to get this maximum value.

To do this, we swap the first one and the last one. At this point, we need to make it bubble its way down to its final position, and that’s what pop_heap does. And if we want to remove, actually remove that value, we pop it back from the vector.

If we pop each value from heap, then we get a sorted collection, and that is what std::sort_heap.

SORTING

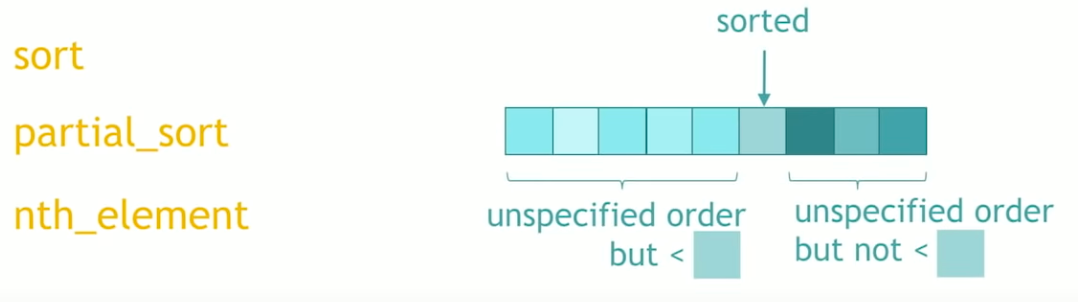

std::sort

Rearrange the collection, and we get a sorted order collection.

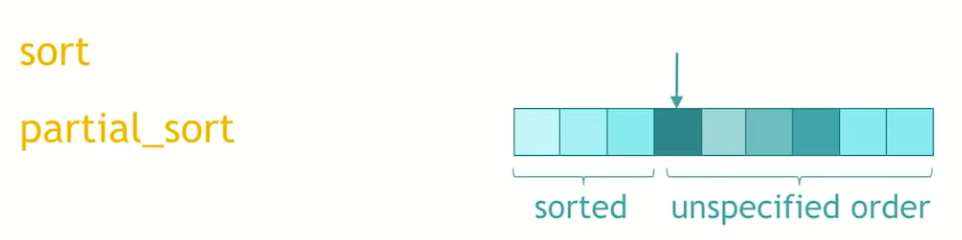

std::partial_sort

Now if we only want to sort the beginning of a collection, this is a partial_sort. partial sort is kind of like a middle, something inside of the collection, and sorts the collection from the beginning to that point, and the rest is in unspecified order.

std::nth_element

nth_element is a partial sorting algorithm that rearranges elements in [first, last).

1 | // Since C++20 |

std::sort_heap

std::inplace_merge

inplace_merge is the incremental step in a merge sort. Merges two consecutive sorted ranges [first, middle) and [middle, last) into one sorted range [first, last).

1 | // Since C++17 |

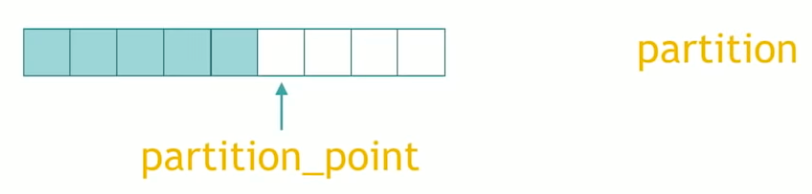

PARTITIONING

To partition a collection is to look at it through a predicate, something that returns a Boolean. If the blue is the predicates. The original collection is depicted as follows.

Then we do partition, then the predicates are at the beginning, and other not-blue ones at the end.

The border between the blue ones and the not-blue ones is called a partition point, that’s the end of the blue range and that’s also the beginning of the not blue range.

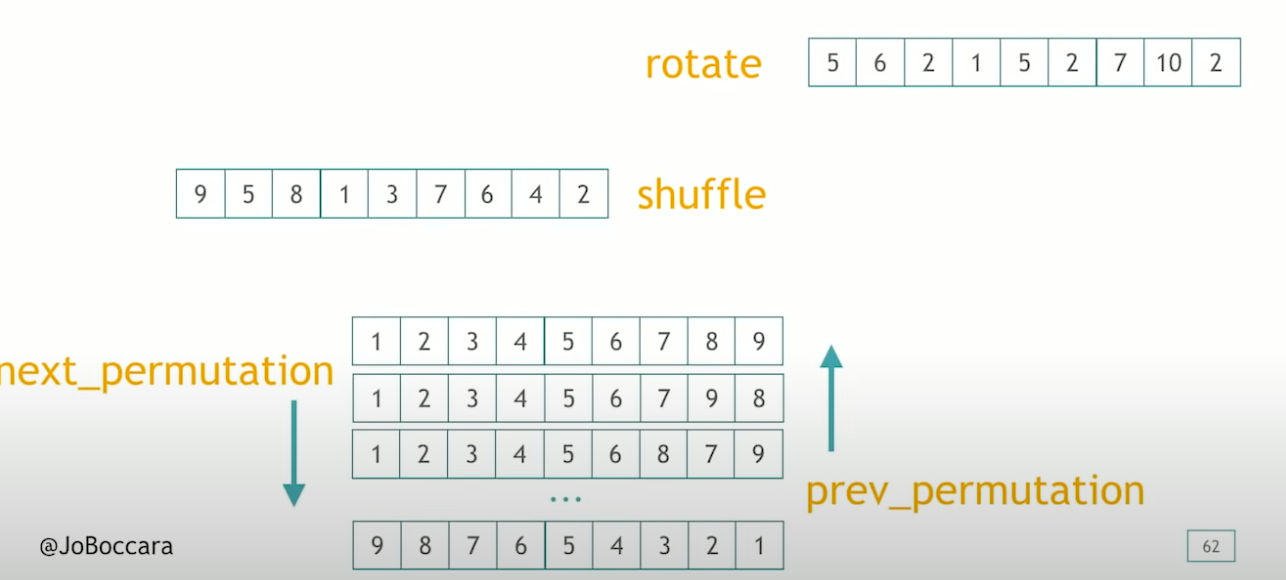

PERMUTATIONS

The elements move around the collection, even if they don’t change value.

std::rotate

1 | // since C++11 and until C++20 |

Performs a left rotation on a range of elements. Specifically, std::rotate swaps the elements in the range[first, last) in such a way that the element n_first becomes the first element of the new range and n_first - 1 becomes the last element.

std::shuffle

std::shuffle is used to randomly change elements in a container. So std::shuffle takes a collection with elements in a certain order, and takes something that generates random numbers, and rearranges the collection in random order.

std::next_permutation/std::prev_permutation

Given a collection of object, we can order them, order all their possible arrangements, and an intuitive way to see that is thinking about an alphabetical order.

1 | // until C++20 |

Permutes the range [first, last) into the next permutation, where the set of all permutations is ordered lexicographically with respect to operator < or comp. Returns true if such a “next permutation” exists; otherwise transforms the range into the lexicographically first permutation (as if by std::sort(first, last, comp)) and returns false.

That’s interesting for every possible arrangement of a collection, we can repeatedly call std::next_permutation until you’ve cycled back to the beginning.

SECRET RUNES

The secret runes are things that you can combine with other algorithms to generate new algorithms. I called them runs because it’s like going to see runes to augment your powers and also because I find that kind of cool as a name.

PARTITIONING-SORT-HEAP

stable_* rune

When we will see all the algorithm that go with the stable rune, so stable when you tack it onto an algorithm, it does what this algorithm does, but keep the relative order. Think std::partition for example, it put all the blue ones at the beginning that’s for sure, but maybe in the process, some of them got swapped around. With std::stable_partition, they all keep the same relative order. Same thing with std::stable_sort.

1 | stable_* ---> stable_sort |

is_* rune

The is_* rune checks for a predicate on the collection. We know what sort, partition, heap, means is_sort/is_partition/is_heap and returns a boolean. To indicate whether it’s a sorted/partitioned/heap that we are looking at.

1 | is_* -----| is_sorted |

is_*_until

is_*_until returns an iterator that’s the first position where that predicate doesn’t hold anymore. So for example, if we have a sorted collection, and then we call std::is_sorted_until we’ll get the end of that collection.

1 | is_*_until -----| is_sorted_until |

QUERIES

So one thing you can extract out of a collection is some sort of value.

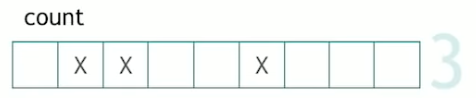

std::count

For example, the simplest one is probably std::count that takes a begin and an end a value, and returns how many times this value occurs in the collection.

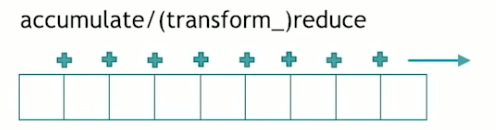

std::accumulate/(transform_)reduce

The accumulate makes some elements of the collection calling operator plus, or any custom function you’d pass it. In C++17, there’s std::reduce appeared, that does practically the same thing as accumulate, except it has a slightly different interface. It can accept to take no initial value, and it can also be run in parallel, but essentially, it’s the same as std::accumulate.

std::transform_reduce takes a function and applies that function to the element of the collection before calling the reduce.

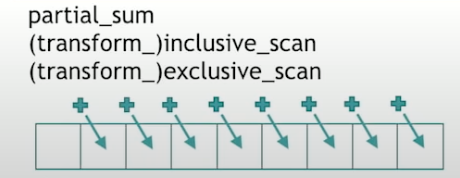

std::partial_sum

I think this is the pre-sum algorithm in std algorithms.

1 | // until C++20 |

std::partial_sum, it sums the all the elements starting from the beginning to the current point of the collection. So here, partial_sum would return a collection with, in the first position, what was in the first position of the original collection. and the second one would plus the seco

Computes the partial sums of the elements in the sub-ranges of the range[first, last) and writes them to the range beginning at d_dirst. This is equivalent operation:

1 | *(d_first) = *first; |

In C++17, there are std::(transform_)inclusive_scan and std::(transform_)exclusive_scan. inclusive_scan is the same thing as partial_sum, except it can run in parallel. exclusive_scan is the same as inclusive_scan, except it doesn’t include the current element. So for example, with exclusive_scan, the second value is the same to the first element of the original collection. The third would be one plus second, so-on and so-forth.

1 | // *(d_first) = ; |

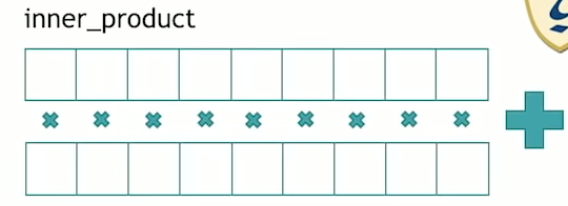

std::inner_product

TODO

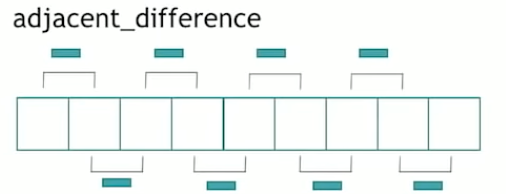

std::adjacent_difference

TODOstd::adjacent_difference makes the difference between every two neighbors in the collection .

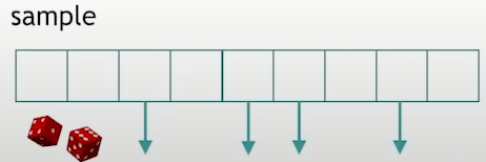

std::sample

std::sample, introduced since C++17, takes something that can return some, that can generate random numbers, and it takes a number, say N, and it produces n elements of that collection, selected randomly.

1 | template <typename PopulationIterator, |

Selects n elements from the sequence [first, last)(without replacement) such that each possible sample has equal probability of appearance, and writes those selected elements into the output iterator out. Random numbers are generated using the random number generator g.

If n is greater than the number of elements in the sequence, selects last-first elements.

The algorithm is stable only if PopulationIterator meets the requirements of LegacyForwardIterator.

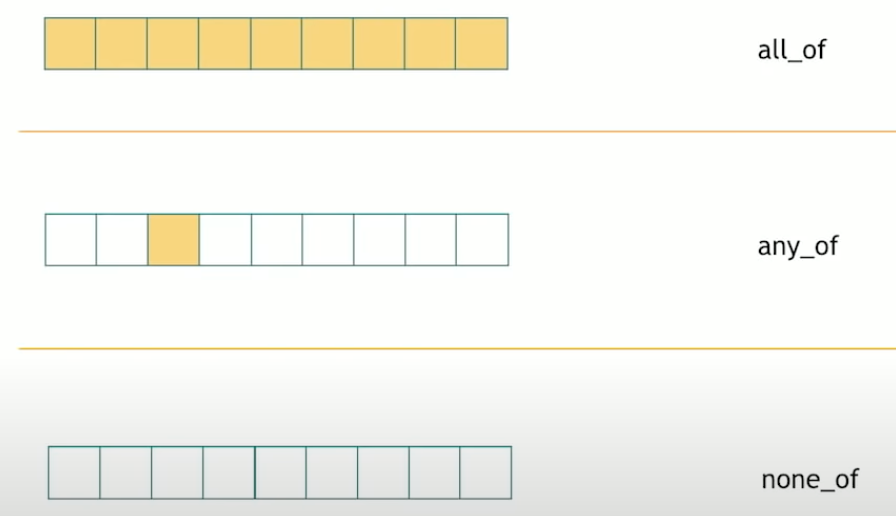

QUERYING A PROPERTY

There are three std algorithms: std::all_of, std::any_of, std::none_of. These three functions are really useful in everyday code.

std::all_oftakes collection and a predicate, returns if all elements satisfy that predicate. If the collector is empty,std::all_ofreturnstrue.std::any_ofat least one element satisfy that predicate. If the collector is empty,std::any_ofreturnsfalse.std::none_ofif no element satisfy that predicate. If the collector is empty,std::none_ofreturnstrue.

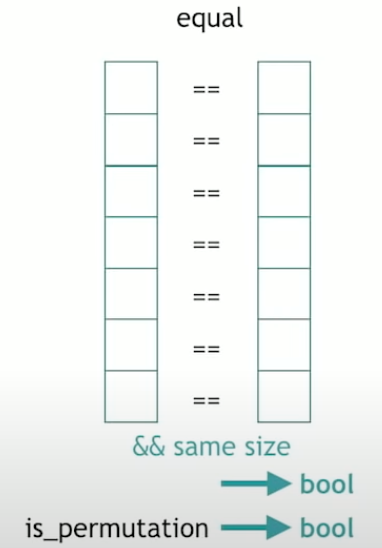

QUERYING A PROPERTY ON 2 RANGES

We can also query a property on two ranges, which is essentially different ways of comparing them.

std::equal

The simplest way to compare two ranges is to see if they have the exact same contents, and returns the boolean result.

Besides, we’d like to know if the two collections contain the same elements but not necessarily in the same order, that’s std::is_permutation.

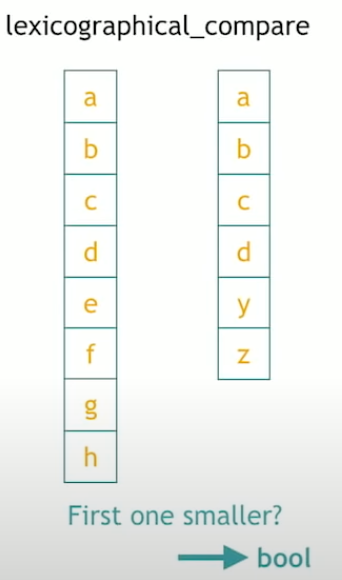

std::lexicographical_compare

Now we can also compare ranges and say which one is smaller than the other one. To define the smaller, we could go with size. That’s not very precise, there’s another way to do that is going back to the alphabetical, lexicographical ordering.

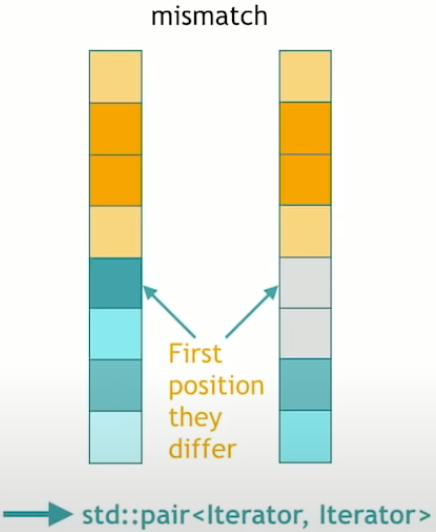

std::mismatch

The last algorithm of comparing two ranges is to traverse them both and stop whenever they start to differ. This is std::mismatch. And returns the std::pair<Iterator, Iterator> iterators pointing to the respective position of where they start to differ in the two collections.

SEARCHING A VALUE

A classic thing to extract in a collection is a position, like looking for something, or to look for something in a collection now, essentially, two ways to do that. It depends on whether the collection is sorted or not sorted. If it’s sorted, we can use a binary search. If not sorted, we have to go through the collection from the beginning.

std::find

std::find takes begin, end and value, and returns the iterator where pointing to that value, or end if that value is not found. Now, it has a sort of like twin brother that’s much less famous, but quite useful as well, and it’s called std::adjacent_find, and that returns the first position where two adjacent value occur and are equal to the value search. So std::adjacent_find takes a beginning and an end and a value and returns the first position where two of those values appear in a row.

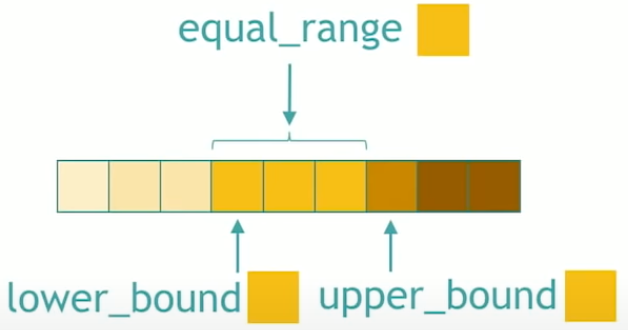

On the sorted range, we are not really looking for a value, because searching for a given value, it could be at several places, and since it’s sorted, they would be lumped together.

std::equal_range: returns a sub-range which all elements in this sub-range are equal to the given value.std::lower_bound/std::upper_bound: and that only indicate position to insert elements.

std::binary_search: It takes a beginning and an end and a value, and only tells you whether it’s there or not, but doesn’t tell you where it found it. And it uses a binary search which is a good thing.

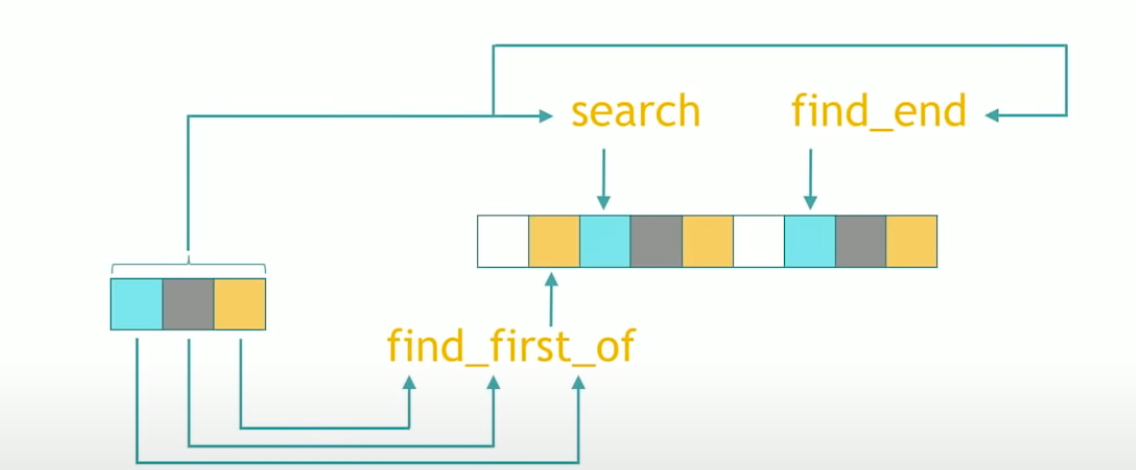

SEARCHING A RANGE

It is looking for a sub-range in a bigger range. To do that, there’s an algorithm that has a very bizarre name, because it’s called search. Search says it will try to find it. It searches a sub-range into a range.

std::search: Searches for the first occurrence of the sequence of elements [s_first, s_last) in the range [first, last).std::find_end: Searches for the last occurrence of the sequence [s_first, s_last) in the range [first, last).std::find_first_of: Searches the range [first, last) for any of the elements in the range [s_first, s_last).

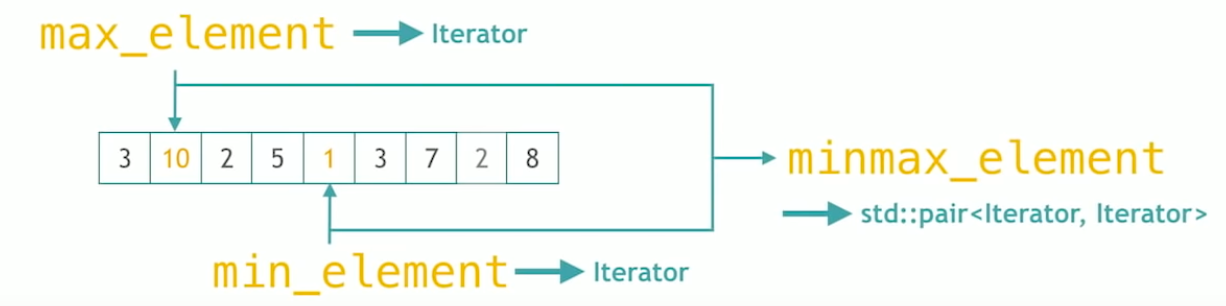

SEARCHING A RELATIVE VALUE

std::max_element: Finds the greatest element in the range [first, last). Elements are compared using operator<. Or elements are compared using the given binary comparison functioncomp. It returns an iterator which points to the max element.std::min_element: Finds the smallest element in the range[first, last). It also uses either operator<or given binary comparison functioncomp. It returns an iterator which points to the min element.std::minmax_element: Finds the smallest and greatest element in the range [first, last). It uses operator<or specified comparison functioncomp. It returns a pair consisting of an iterator to the smallest element as the first element and an iterator to the greatest element as the second. Returnsstd::make_pair(first, first)if the range is empty.

ALGORITHMS ON SETS

What is sets? It includes std::set, but not only. In C++, we call any sorted collection as set. So a std::set is sorted and is a set, but sorted vector, for the purpose of the STL algorithms, is also considered as a set.

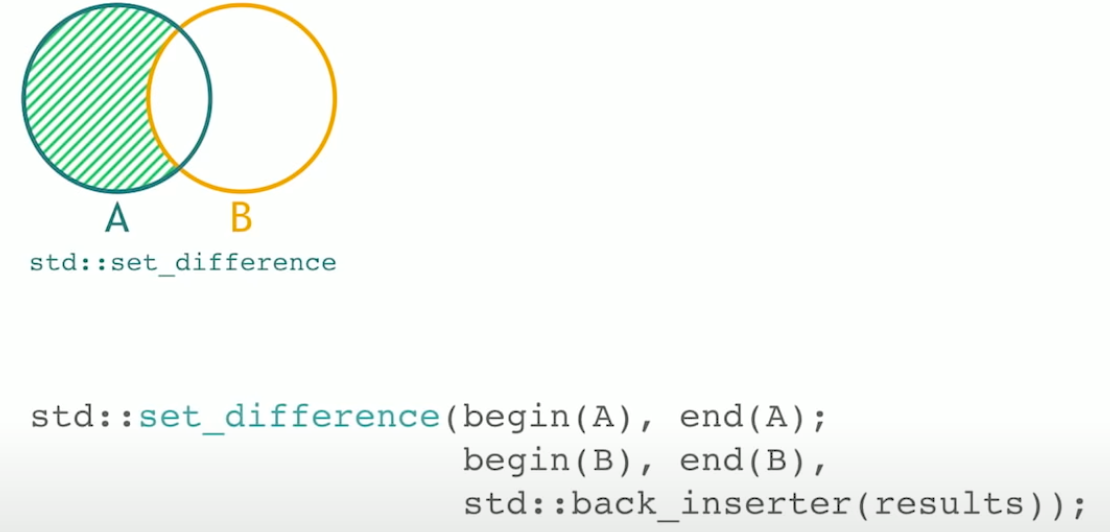

std::set_difference

Copies the elements from the sorted range [first1, last1) which are not found in the sorted range [first2, last2) to the range beginning at d_first.

1 | // Until C++20 |

This is a common usage like this. During set_difference, the new value would be push_back into the result vector. It’s an inner complexity because it uses the fact that the input that sorted and also its output is sorted.

1 | std::vector<int> results; |

std::set_difference

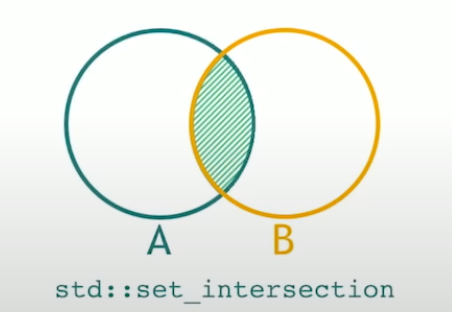

std::set_difference has siblings std::set_intersection that returns collections that they are both in A and B sets.

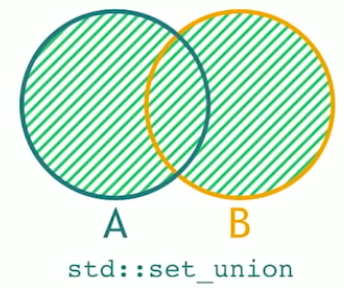

std::set_union

std::set_union returns elements that are in A or B.

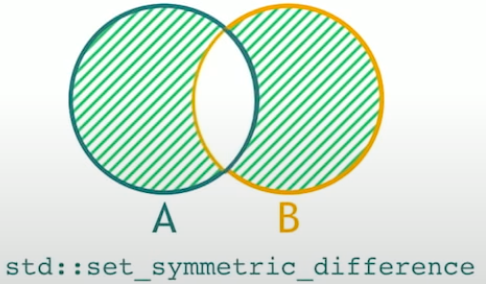

std::set_symmetric_difference

std::set_symmetric_difference that returns the elements are in A and not in B and those that are in B and not in A.

std::includes

std::includes that returns a boolean that indicates whether all the elements of B are also in A.

std::merge

std::merge that takes two sorted collections, and puts them together into one big sorted collections.

MOVERS

Movers are algorithms that move thins around.

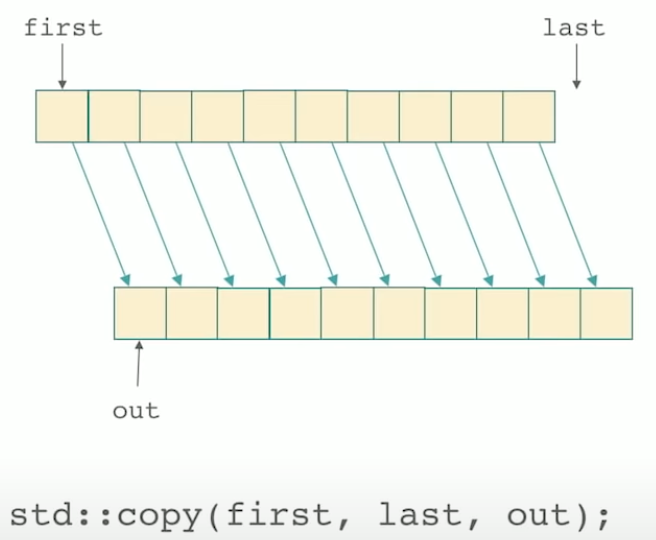

std::copy

The simplest way to move things around is probably to copy them.

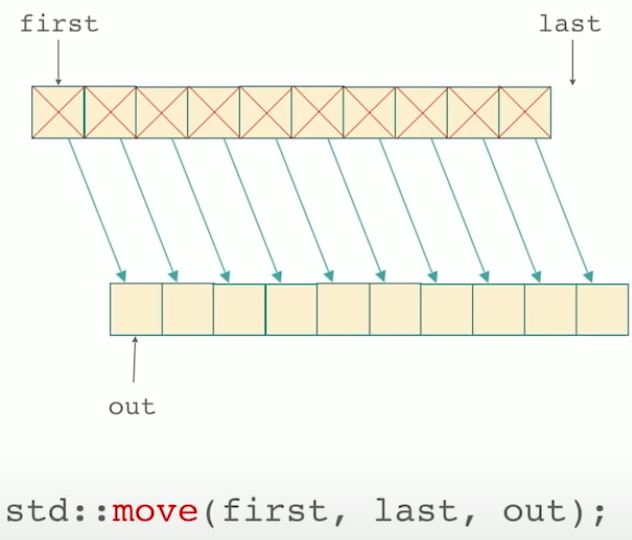

std::move

std::move is the algorithm that it takes a beginning and an end and an output iterator just like std::copy

1 | // Since C++11, until C++20 |

Moves the elements in the range [first, last), to another range beginning at d_first, starting from first and proceeding to last - 1.

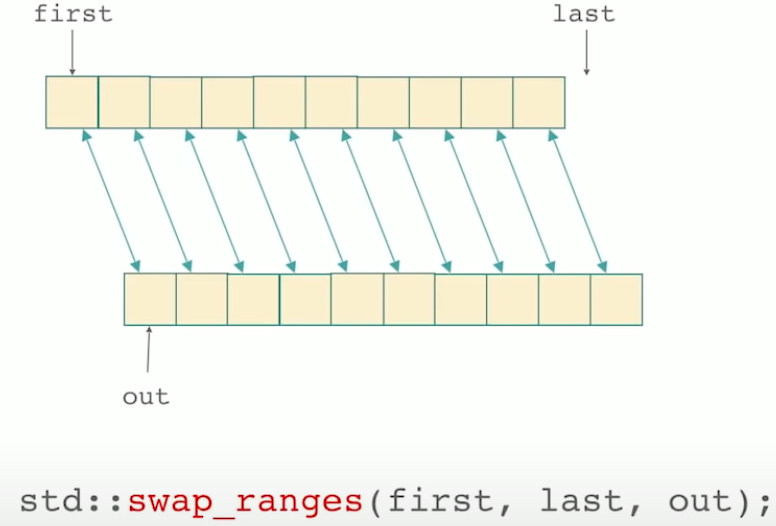

std::swap_ranges

std::swap_ranges swap the contents of two ranges. Obviously have to be the same size.

std::copy_backward

1 | // Until C++20 |

Copies the elements from the range, defined by[first, last), to another range ending at d_last. The elements are copied in reverse order (the last element is copies first), but their relative order is preserved.

The possible implementation is like this:

1 | template <typename BidirIt1, BidirIt2> |

This is as same as std::move_backward except std:move_backward moves elements to the new container.

VALUE MODIFIERS

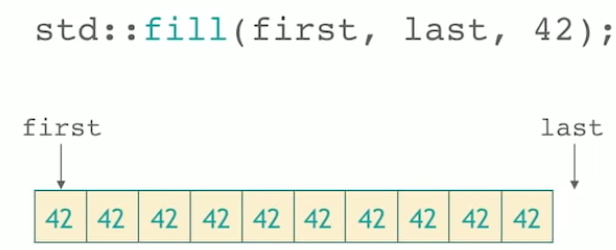

std::fill/std::iota/std::generate/std::replace, these four algorithms actually changes the collection.

std::fill

std::fill puts the same value in every collection.

std::generate

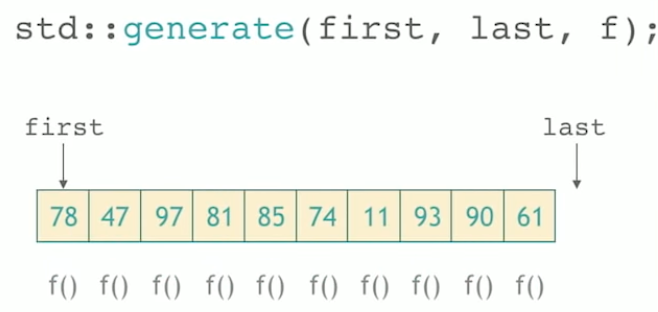

std::generate uses a function that can be called with no arguments, and we call that function once for every element of the collection.

std::iota

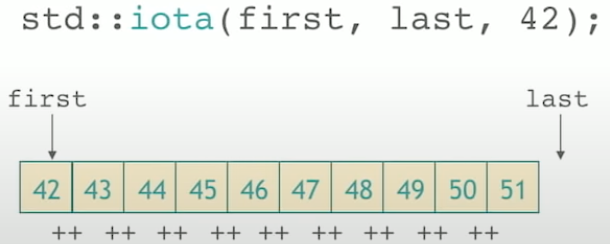

std::iota is the another to feed a collection and that’s quite useful to have a quickly a sequence of values std::iota(pronounce: io-ta). It put that value at the beginning and then increment it and increment it until it fills the whole collection with increments.

std::replace

std::replace replaces the values in a collection like replace 42 to 43 in the whole collection std::replace(first, last, 42, 43);.

STRUCTURE CHANGERS

These algorithms that after I’ve down that drove the collection does not look the same even from a far so. There are two of them std::remove and std::unique.

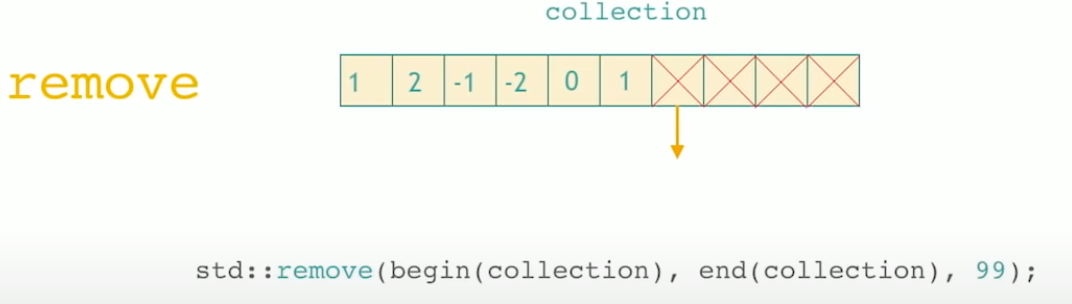

std::remove

std::remove is used to remove values but has something peculiar with it since STL algorithms only access the iterators of a collection and not the collections themselves. They can not change the size. So the std::remove does is to pull up the collection by leaving only those that should not be removed. So if we want to remove a value, we use to remove this value, and pull up other values. And what is at the end is not specified. We can’t rely on it. This depends on compiler how to do this.

std::remove returns an iterator that points to the first that’s crossed out.

1 | // erase all values that equals to 99. |

std::erase

Erase all elements that compare equal to value from the container.

1 | // Since C++20 |

This is equivalent to the following code:

1 | auto it = std::remove(coll.begin(), coll.end(), value); |

Erases all elements that satisfy the predicate pred from the container. Equivalent to:

1 | auto it = std::remove_if(coll.begin(), coll.end(), pred); |

Returns the number of erased elements.

std::unique

1 | collection.erase(std::unique(std::begin(coll), |

*_COPY

We have seen all the algorithms that are combined with _copy in the STL algorithms library. You can tack it on an algorithm like those algorithms, it creates new algorithms that do the same thing but in a new collection, like remove or unique or replace or whatever, they operate in-place. Those _copy version, they leave the collection untouched and they take an output iterator, and they produce the output to that output iterator.

1 | std::remove_copy |

*_IF

*_if acts like a predicate. For example, find, std::find_if takes a value, and a predicate.

1 | std::find_if |

LONELY ISLANDS

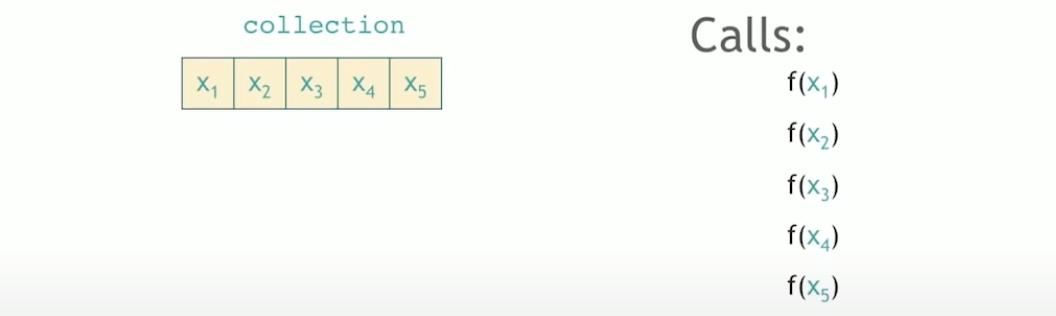

There are two algorithms: std::for_each and std::transform.

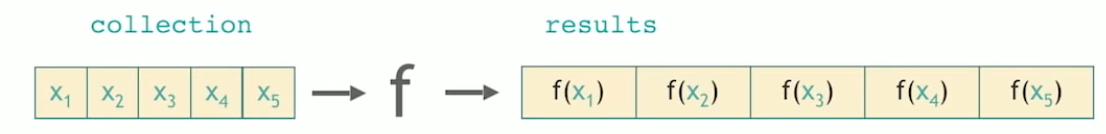

std::transform

std::transform applies a function to the elements of a collection. So it takes a collection, begin, end, a function f, and an output like an output iterator. And it produces the application of that function to every element of the collection.

1 | std::transform(std::begin(coll), std::end(coll), |

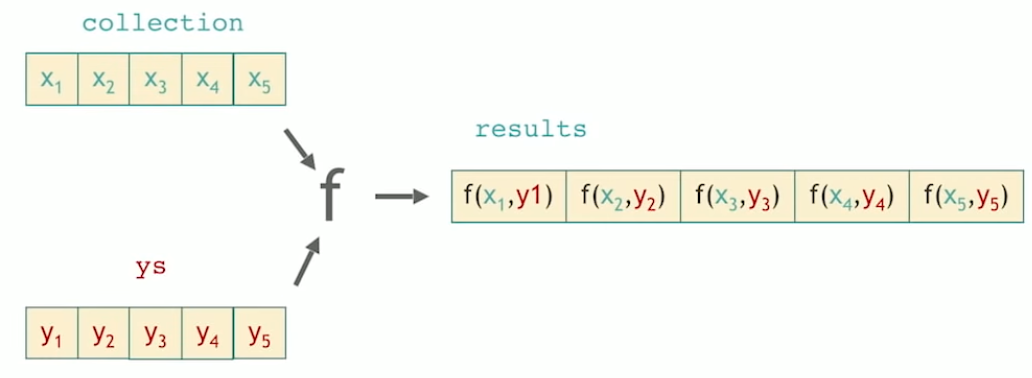

What’s a bit less famous about transform, it can take two collections as parameters. It applies that function just like transform with one input collection to the two collection by feeding the two collection into f for each element and producing the output.

1 | std::transform(std::begin(coll), std::end(coll), |

For example, if you like to sum the elements of two collection two by two, you can do that with one line of coding with transform and function f is std::plus which in the <functional> header file.

std::for_each

std::for_each takes a beginning, and an end, and some piece of code, a function, it could be a lambda or a regular function. So for puror of for_each, f might as well return void.

std::for_each is made to perform side-effects.

Using std::for_each for making anything else, such as a partition or a find or whatever, is not the right usage of for_each. There are algorithms that are more appropriate than for_each, and if there’s no algorithm more appropriate than for_each in the STL algorithms, then the algorithms outside of the STL algorithm.

1 | // Until C++20 |

This Applies the given function object f to the result of de-referencing every iterator in the range [first, last), in order.

The possible implementation is like this.

1 | template <typename InputIt, typename UnaryFunction> |

1 | std::for_each(std::begin(coll), std::end(coll), f); |

RAW MEMORY

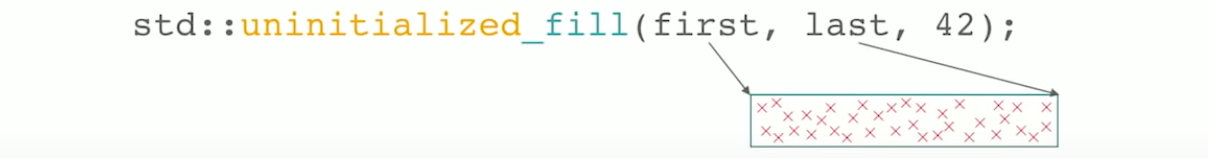

There are three algorithms, std::fill/std::copy/std::move, which are performed on raw memory. They have one thing in common, it’s that they use the assignment operator.

1 | std::fill -> operator= ---> uninitialized_fill (calls ctor) |

Now if we use an assignment operator, it means that the object has been constructed, and hopefully that’s true. But in some rare cases, we have objects that are not constructed yet. If we have just the memory, just chunks of memory that we got from somewhere, and we’d like to construct instead of calling the assignment operator, we’d like to call constructor on those chunks of memory. For that, we use the unitialized counterpart. This is the constructor that takes a value. So, in practice, you get a chunk of memory from somewhere, like shared memory or wherever. And you would like to fill it with values but you can’t call fill because you can’t call the assignment operator because there is just raw memory, it hasn’t been initialized yet. So we need to call the constructor. This is what std::unitialized_fill does. It takes two pointers for at the beginning and the end, and calls the value constructor, leading to an initialization of that chunk of memory.

Now, once we are done with it, we want to call the destructor, if we are in charge to call the destructor. That’s what std::destroy does. But we don’t really use it on a day-to-day basis.

std:::destroy(first, last)

The definition of std::unitialized_fill is as follows.

1 | template <typename ForwardIt, typename T> |

Copies the given value to an uninitialized memory are, defined by the range[first, last) as if by:

1 | for (; first != last; ++first) |

Where /*VOIDIFY*/(e) is:

1 | static_cast<void*>(&e); // until C++11 |

The possible implementation is as follows.

1 | template <typename ForwardIt, typename T> |

The examples:

1 |

|

Another case is as follows:

1 |

|

*_N

1 | copy_n |

For example, we perform the std::fill on a collector. If we use std::fill_n takes beginning, size, and a value, and it fills the first five elements starting from the beginning.

1 | std::fill(std::begin(coll), std::end(coll), 42); |

1 | // This fills 5 elements in coll with 42 |

1 | std::fill_n(std::back_inserter(coll), 5, 42); |

CONCLUSION

STL algorithms can make code more expressive. There are serval tips for your code to use STL algorithms more.

- Replace your

for-loops by the right algorithm.

By an STL algorithm to make it smoother to work with. - More algorithms

Boost.Algorithms:gather,sort_subrange,is_palindrome,boyer_moore,one_of, etc. - Understand in depths the STL algorithms.

Algorithmic complexity

Pre/post - requisites, like think about sorted collections for example.

Look at the implementation. See how they are implemented, that is often quite instructive. - Get inspired. If you can get inspired, you can have a better intuition of what abstractions work well. That’s the fundamental of writing code, and that intuition, you can use that in our own code. Once you are familiar enough, you can start thinking about writing your own algorithms. Well, we can combine an algorithm, an existing algorithm with a rune, like

sort_copydoesn’t exist. Besides, you can enrich a family, likeset_segregate. Also, you can start a new STL family.

C++ STL Overview